- Home

- Sheela Chari

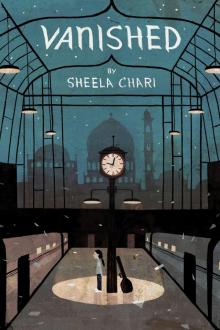

Vanished

Vanished Read online

Text copyright © 2011 by Sheela Chari

Illustrations © 2011 by Jon Klassen

All rights reserved. Published by Disney •Hyperion Books, an imprint of Disney Book Group. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information address Disney •Hyperion Books, 114 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10011-5690.

Designed by Joann Hill

ISBN: 978-1-4231-5260-6

Visit www.disneyhyperionbooks.com

Table of Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Epilogue

Author's Note

Acknowledgments

For my mother

It was close to midnight when the last train left the station. On board sat an American woman in a fluttery shirt, a famous musician on her way to the biggest music festival in Chennai. But the festival wasn’t the reason she was in India after so many years. If she could go back to the store, the shopkeeper might have the answer she was looking for.

Outside the air grew damp and foggy as the train rumbled through the darkness. The woman closed her eyes and fell asleep next to her husband, but not before wrapping her arm tightly around the instrument case on the other side of her.

At dawn the fog thickened, creating a beautiful mist over the countryside. The fog was also nature’s way of covering up dusty village streets, roaming animals, and makeshift huts, brown with filth.

And then the unthinkable happened.

Several hundred feet ahead of the moving train, a large wispy mist, which wasn’t mist after all but something more solid, crept across the tracks. The engineer slammed the emergency brakes, but that didn’t stop the train from striking the cow, or from derailing and plunging into a ditch.

Rescue workers arrived on the scene, pulling out survivors from the wreckage. At the end of the day, one of the workers made a strange discovery.

Everyone gathered around as he unzipped the torn cover of what seemed to be an instrument case. “Not a crack, not a dent,” he said in surprise.

The others stared at the stringed instrument and the figure on the peg box, which was different from anything they had ever seen. The case had been found in a car where none of the passengers survived. It seemed like a miracle, but no one was sure if it was an act of God or something sinister.

“Could it be?” wondered someone.

“Rubbish,” said his supervisor, who didn’t believe in curses.

But when the man came later to add a tag, the case was gone. Exhausted, he looked around the shadowy field as best as he could, then gave up and went home. It would be easier to search in the morning hours when there was light.

The next day came, but no more thought was given to the missing instrument, and it was soon forgotten, having never been officially recorded anywhere. Instead, its journey continued, passing through many hands, sounding lovely for those who could hang on to it.

There was no place in Ms. Reese’s sixth-grade class to form a circle. So when their teacher announced that they needed to make room, everyone pushed back their desks and chairs with a great clatter, curious to know what required so much space. Neela, who saw an ocean of blue carpeting open around her, wondered if she had made a big mistake.

“Dude, is that a harp?” Matt asked.

A harp! Hardly. Neela glanced at her friend Penny, who shrugged.

“A harp’s flat, stupid,” Amanda said. “That thing looks big and lumpy.”

“Amanda,” Ms. Reese reproached gently.

Neela unsnapped the case and pulled out her instrument.

The class leaned in to have a look.

“This is my veena.” She was going to add that it belonged to her grandmother until six months ago, when it literally arrived on her doorstep from India. But her knees began to shake, so she sat down and crossed her legs lotus-style, hoping no one would notice.

“So tell us more.” Ms. Reese flashed her smile where the skin crinkled around her eyes. It was the smile she reserved for students who were about to humiliate themselves.

Neela looked through her note cards. Would anyone want to know about Guru, the veena maker who put his initials on the neck of every instrument he made, and that she might even have a “Guru original”? She decided to stick with the first card. “A veena is a stringed instrument from India,” she read, “dating back to the eleventh century. It’s made from jackwood, and played by plucking the strings.”

“What’s on the top where the strings are connected?” Matt asked. “It looks like a ninja.”

“It’s a dragon.” In spite of her shaky knees, Neela fingered the peg box proudly. “All veenas have some kind of animal decoration. It’s for luck.”

“Would you like to play something for us?” Ms. Reese asked. There was that smile again.

Actually, that was the last thing Neela wanted to do. She had heard about how some musicians got stage fright, but she was sure that what she had was far worse. At home she could play all the notes, and sometimes when she closed her eyes, she imagined herself in a concert hall with hundreds, even thousands of people watching her. But if there was a real, live person in the room other than her parents or her little brother, something happened, as if her notes stuck together and became an out-of-tune, out-of-rhythm mess. Something happened to her, too—shaky knees, a dry throat, and once or twice, she saw spots.

Sudha Auntie said the best cure was to keep playing in front of people. “It will teach you,” she said, “to forget your nerves.”

Neela wasn’t sure about Sudha Auntie’s theory. Just this summer, she was on the stage at the temple before her family, friends, and what seemed like the entire Indian community of Boston. She was performing for the first time on her grandmother’s veena, when halfway through, a string suddenly snapped, nearly whacking her in the face. Her teacher hissed from backstage, Keep going. But Neela could not keep going; she could only look helplessly at the tittering audience. Did people laugh at an eleven-year-old mortified onstage? Yes, they did.

With that performance fresh in her mind, Neela didn’t understand how she could end up bringing her veena to school. Last week when Ms. Reese announced the Instruments Around the World unit, a bunch of kids raised their hand to bring instruments no one had seen before: a Chinese dulcimer, a Brazilian berimbau, even a set of Caribbean steel drums. In the midst of all that hand-raising, Lynne, the new girl, turned to Neela and said, “Don’t you have that really big Indian instrument? I heard you telling Penny about it.” Then, before Neela knew it, she had volunteered to bring her four-foot veena to school. So here she was, with her veena, her nerves, and the whole of Ms. Reese’s class watching her. Neela took a deep breath and began.

She was aware of everyone in the classroom. Penny was in the front, sitting with her

feet tucked under her, as she always did. Amanda was in the back, whispering something hateful to the girl next to her. Matt was already starting to fidget. He was rocking slightly, tossing back that strange hair of his, bleached to a startling shade of orange. Then there was Lynne, the girl who had joined their class this year—was she really taking pictures? Next to them all, Ms. Reese was poised to shush, poke, prod, threaten, and restrain—whatever it took to force the class to listen to Neela until she was done.

The song was a short one Neela had learned last year about the goddess Lakshmi. There was that run of notes in the beginning and the slide all the way down to sa that she loved because it was like falling fast, sudden, and landing with both feet on the ground. The next notes, the high ga-ma-pa, were always impossible to hit. And then as she continued, she noticed the sound of her grandmother’s veena, which was normally so rich and woody, became twangy—maybe the room was too cold? The more she listened, the more distracted she became by the twanginess, so that her fingers forgot what they were doing. Every time she made a mistake, her face heated up until she was sure her cheeks were as pink as Amanda’s painted fingernails.

“Thank you,” Ms. Reese said to the beet-faced Neela when it was over. “What a treat.”

“Good job, Neela,” Penny said, flashing a smile full of braces at her. But that was because, nice as Penny was, she didn’t know a thing about how Neela felt after playing in public.

Neela tried to ignore the disappointment that filled her. It was as if there were two Neelas—the imagined one that played before hundreds of people, beautifully and effortlessly, who could hit the high ga-ma-pa every time. And the real one. With the shaky knees. The one who skipped notes, whose string snapped in public.

At least she didn’t snap a string this time. She began to put away her veena, then stopped in surprise when she saw a small group around her.

Matt was the first person who asked to try her veena. He strummed a few notes, then pretended to do a rock-star riff. “You should get this wired and plug it into an amp. An electric veena—that’d be awesome.”

“Yeah,” Neela said, though it was the weirdest suggestion she had ever heard.

Penny was next. “How do you even lift the whole thing?” she asked.

“It’s big, but it isn’t heavy. It’s mostly hollow. See?” Neela showed Penny by raising the veena up with one hand.

“Can I try playing?” Amanda asked.

Neela was surprised. Amanda, the girl who changed her nail color every day, who still called Neela “Salad Head” because she wore coconut oil in her hair maybe once in third grade? Interested in her veena?

“Um, sure,” Neela said. She felt a cloud of fruity perfume envelop her as Amanda bent down, plucking each string with a single, nail-polished finger.

“What’s this mark?” Amanda asked.

“It looks like a scratch,” Penny said.

“Oh, that. It’s the veena maker’s initials. My teacher says the veena is a Guru original.” Neela couldn’t help flushing with pride.

Amanda nodded, not all that interested. “I was talking to my mom,” she said, “and I might have a—” Before she could finish, she yelped, pulling her hand back from the floor.

Behind her stood the last person waiting for a turn. Lynne had knelt down with her camera, not noticing she had stepped on Amanda’s hand. “Your veena is cool. I love the dragon,” she gushed to Neela. She took a few shots from different angles.

Amanda stood up, glaring.

“Nice, uh, camera,” Neela said.

Lynne sniffed. “It’s junk. What I really want is an SLR with a telephoto and zoom lens.”

Neela blinked.

“Someone needs to wear thicker glasses,” Amanda announced loudly to Penny, while rubbing her hand. Penny glanced at Lynne to see what she’d say.

Lynne’s eyes flashed behind her tortoiseshell frames. “Someone needs to wear less hairspray,” she retorted.

Before Amanda could answer, Ms. Reese asked everyone to move their desks back. “Amanda, Penny—that means you. Lynne, time to put away the camera.”

Penny returned to her desk. So did Amanda, but not before glaring at Lynne, who stuck out her tongue at her.

“I guess you must really like your veena,” Lynne said as Neela put the veena away.

“Um, sure. It’s my grandmother’s. She gave it to me.”

“So you’ll play on it for a while and sell it afterward, huh?”

Neela sat back on her heels. “Why would I sell it? It’s my grandmother’s!”

“Oh yeah, right.”

Neela watched as Lynne returned to her desk, brushing an explosion of curls from her face. From her desk she pulled out a notebook and wrote something down.

Strange, Neela thought. But Lynne was a strange person in general. She didn’t talk much to anyone, although sometimes she would smile and say a few words to Neela. Most of the time she was writing stuff in her notebook or doodling on the back cover. At recess she would take photos of dandelions or cracks in the pavement or anything else that most people didn’t bother looking at.

Neela sat down at her desk, thinking again about her performance. Whenever she felt depressed about her playing, she tried to remember Lalitha Patti, her grandmother, who had mysteriously mailed the veena to her a few months ago.

Lalitha Patti was the other musician in the family and the reason Neela chose to learn the veena three years ago. Her grandmother wasn’t a professional and hadn’t given a public performance in her life. But she loved the veena and owned several, which she kept on stands in a separate room in her house. When Lalitha Patti played, the world seemed to stop. So intense and focused was her playing that she hardly seemed to know anyone else was in the room.

Once her grandmother stared in amazement as Neela tried to explain stage fright to her. “Why do you have to play in front of anyone at all?” Lalitha Patti exclaimed.

“But I thought…” Neela’s voice trailed off because she didn’t know what she thought.

“Shut yourself off in your room,” Lalitha Patti said. “Learn to play for yourself first, and the rest will come. You’ll see.”

Play for yourself. Neela remembered those words now as she sat at her desk. What Lalitha Patti said made sense. Still, what was the point of having a beautiful veena if you were too scared to play in front of anyone?

Outside, the October sky turned dark as Neela started home, the wheels on her veena case squeaking against the pavement. The case, designed by her father’s friend, was a hard plastic shell covered with thick canvas, but the wheels made it easy to drag. Some days she walked with Penny, but most of the time she walked by herself because Penny got a ride with her mother. But Neela didn’t mind. It gave her a chance to reflect over the day before she got home.

As she walked today, she thought about the way the veena had first come into her life. It was a Saturday morning in April. The tulips were in bloom, with splashes of yellow and pink along the walkway behind the mailman who came to deliver the package. He brought it inside, and after her mother signed for it, the whole family crowded around, wondering what on earth it could be.

The box was large and padded, bigger and taller than Neela, with Fragile and words in Hindi stamped across several places in purple ink, smudged but official-looking. The package was addressed to her from Lalitha Patti, care of Chennai Music Palace.

When Neela opened it, the whiff of India assailed her nose—that mysterious combination of laundry detergent and mothballs and coconut oil. After digging through layers of Bubble Wrap and foam, her parents helped her pull out a veena and set it on the wooden floor of their living room. On the ground, it rocked slightly from side to side, as if impatient to begin its new life in Arlington.

“Chennai Music Palace?” Mrs. Krishnan said, amazed. “Your mother bought Neela a new veena?”

But Neela had recognized the instrument right away. “Not a new veena!” she exclaimed. “It’s one of hers.”

Mr. Krishnan looked at the veena and then inside the box to see if there was a note, but except for the packaging, the box was empty. “She didn’t tell me she was mailing anything,” he said, baffled.

“Maybe it has something to do with what happened last month,” Mrs. Krishnan said.

In March, someone broke into Lalitha Patti’s house in India and stole one of her veenas—her most expensive one with inlaid rubies, coral, and emeralds.

“I’m calling my parents,” Mr. Krishnan said. As he dialed, Neela knelt beside the veena, fingering the long neck and sweeping curve of the dragon peg box. Out of all the veenas her grandmother owned, this one was Neela’s favorite. It wasn’t nearly as fancy as the veena with the jewels, and its wood was dark and more faded than all the others in Lalitha Patti’s collection. But it was quite old, with intricate carving along the neck and face, and the frets were made from bronze instead of the customary brass. Most of all, Neela loved the peg-box dragon. Unlike most other veenas that had only a dragon’s head, this one had a complete body with wings folded down and a pair of legs and tail painted along the sides. With its slanting eyes, pointy face, and curling tongue, the dragon was the fiercest-looking one in Lalitha Patti’s collection. It didn’t even seem Indian, but like a creature from the time of King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table.

Neela could hear her father talking behind her. “But why?” he asked. “She’s only been playing for a few years. It’s too fancy for her.” There was a silence as he disappeared into the kitchen, his voice becoming a murmur. Several minutes later he came back to the living room.

“Is it from Chennai Music Palace?” Mrs. Krishnan asked.

“No. She’s friends with someone there who helped her ship it, that’s all.”

Mrs. Krishnan looked at him with more questions in her eyes, but he shook his head. “Here,” he said to Neela. “She wants to speak to you.”

Neela took the phone from him and couldn’t stop talking. “It’s beautiful, my favorite, thank you, how could you know…What made you? Why?”

All to which her grandmother said, “Enjoy, Neela. Just take very good care of it.” For a moment Neela thought she heard something else in her grandmother’s voice, a note of caution. But then Lalitha Patti only said, “And keep up your practicing.”

The Unexplainable Disappearance of Mars Patel

The Unexplainable Disappearance of Mars Patel Vanished

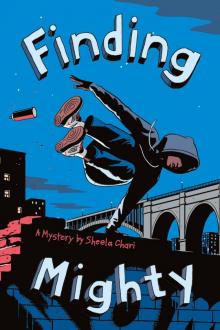

Vanished Finding Mighty

Finding Mighty