- Home

- Sheela Chari

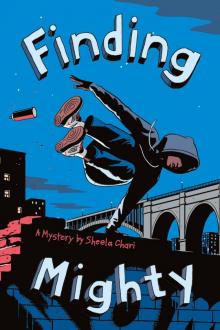

Finding Mighty

Finding Mighty Read online

PUBLISHER’S NOTE: This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Chari, Sheela.

Title: Finding Mighty / Sheela Chari.

Description: New York : Amulet Books, 2017. | Summary: “Along the train lines north of New York City, twelve-year-old neighbors Myla and Peter search for the link between Myla’s necklace and the disappearance of Peter’s brother, Randall. Thrown into a world of parkour, graffiti, and diamond-smuggling, Myla and Peter encounter a band of thugs who are after the same thing as Randall. Can Myla and Peter find Randall before it’s too late, and their shared family secrets threaten to destroy them all?”—Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016042022 (print) | LCCN 2016052878 (ebook) | ISBN 9781419722967 (hardback) | eISBN 9781683350613 (ebook)

Subjects: | CYAC: Mystery and detective stories. | Family life—New York (State)—Fiction. | Graffiti—Fiction. | Parkour—Fiction. | East Indian Americans—Fiction. | Racially mixed people—Fiction. | Dobbs Ferry (N.Y.)–Fiction. | BISAC: JUVENILE FICTION / Family / General (see also headings under Social Issues). | JUVENILE FICTION / Lifestyles / City & Town Life. | JUVENILE FICTION / Art & Architecture.

Classification: LCC PZ7.C37368 Fin 2017 (print) | LCC PZ7.C37368 (ebook) | DDC [Fic]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016042022

Text copyright © 2017 Sheela Chari

Illustrations © 2017 Reid Kikuo Johnson

Book design by Pamela Notarantonio

Published in 2017 by Amulet Books, an imprint of ABRAMS. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Amulet Books and Amulet Paperbacks are registered trademarks of Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Amulet Books are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact [email protected] or the address below.

ABRAMS The Art of Books

115 West 18th Street, New York, NY 10011

abramsbooks.com

for Keerthana and Meera

for siblings everywhere

Back when I was five, I met Peter for the first time. We were at Margaret’s house for dinner, long before she moved to Vermont. There were other kids there, like Peter’s brother and mine, but Peter was the only one who didn’t talk. He kept close to his mom, who had the longest black hair I ever saw, with butterfly clips in it, and I wondered if she was Indian like us.

Peter sat next to me at the table. He was thin, and his hair was curly and dark as black licorice. Sometimes his mom gave him stuff on his plate like potatoes or a bread roll, but mostly Peter sat without eating.

After they left, everyone shook their heads like they were sorry.

Sorry for what? I wondered. There wasn’t much I was sorry about, not at the age of five.

Then I heard the story of what happened to Peter’s dad. I don’t think I was meant to hear, but the adults got to talking and didn’t pay attention to what the kids were listening to. Years later when I saw Peter again, I’d forgotten Margaret’s party. I’d forgotten thinking his hair was like black licorice. But I didn’t forget what happened to his dad. There are some things you never forget.

Maybe it was a coincidence, Peter moving to Dobbs Ferry. Maybe Margaret was the common thread. Or maybe, as Peter says, it was all a kind of magic. For him, it started with the duffel bag. For me, it was the necklace. Actually, it started further back with Rose, and what she did to hide her secret. But I’d have to imagine that part. Instead it’s better to tell what we do know, the part that happened to us.

At the end of August before sixth grade started, Cheetah broke my bed. My best friend, Ana, and I were in the kitchen eating ice cream when we heard a loud crash. We ran upstairs, our cones dripping chocolate mint, and found my nine-year-old brother sprawled on the caved-in mattress, a big, stupid grin on his face. “Sorry,” he said, but he wasn’t.

Mom said, “It was just waiting to happen.”

If you saw my bed, you’d understand why. When I was young, I was afraid to sleep on a real one. So I slept on a mattress on the floor. I liked that fine, until two years ago when I woke up eye to eye with a long, black spider on my pillow. Then I was done with sleeping on the floor. I took a sheet of plywood from the garage, plus some leftover cinder blocks, and I built myself a low bed. I even made a headboard and painted it white with the spray paint we used on our fence.

Dad said proudly, “Myla, my engineer.” That’s because he’s a math teacher, and math people are into building things.

Mom was different. “What if it breaks?” But it didn’t. It held up for two years, until my dorky brother jumped on it and snapped the plywood in two. So now Mom was adamant. “It’s time you had a real bed, Myla. I didn’t go back to work so my children could sleep on cinder blocks.”

I don’t know what the big deal was. But nothing could change her mind, so on Sunday we headed to a furniture store in Yonkers where we bought our dining table last year. I invited Ana because we were going to Spice afterward, and the tandoori pizza there was so good, it was worth buying a bed I didn’t want.

In the car, Ana leafed through a magazine she’d brought. “Look at this cool bed. It has curtains hanging over it from the ceiling.”

“It’s ugly,” Cheetah said. “Plus it’s too tall for Myla. She’d be scared.”

“No, I wouldn’t.” I gave him a shove. Cheetah was always saying the wrong thing.

“And it isn’t ugly,” Ana said. “It’s beautiful.” She tucked her pale hair behind her ears. Ana is Norwegian on both sides—her grandparents are from Norway—but her parents grew up in Seattle. Which makes her American like me.

“I still don’t get why you were jumping on my bed,” I said. My brother was always destroying my stuff, like opening my Harry Potter books too wide until the spines broke, or using up all the ink in my Sharpies. I poked him but he still didn’t answer. For a minute, I thought he was hiding something. But what? Everything he did was an open book. Not like me.

I pulled out my journal from my backpack. It was small, and I used it to record things. Sometimes I write down what’s going on, like, “Cheetah’s jump breaks my bed.” Or I jot down what I see, like a billboard or a piece of graffiti. Once I drew High Bridge, because even though I’m scared of bridges, I liked the way the arches came down to meet the highway, like the legs of gigantic Transformer robots.

Ana records things, too—but she doesn’t keep a journal—she uses her phone to take pictures. She doesn’t care about signs or bridges or words. She takes pictures of horses. She’s crazy about them. She goes riding on Saturdays at a stable on the other side of the Hudson River, and that’s where she takes lots of pictures. She says she wants to be a trainer someday, or a professional horse photographer. I don’t know yet what I want to be. I know it has to do with words, and building things with my hands.

“Mighty,” my brother read from a highway wall, as we took the exit to St. Vincent Ave. So I wrote it down in round letters, even if I already have Mighty in my journal, because it’s my favorite.

St. Vincent Ave is the ugliest and most beautiful street in the world. Dad says it starts in the Bronx and ends in the town of Yonkers. We go there to eat at Spice or to shop for furnit

ure. The stores are close together, with rolling metal gates that pull down when it’s time to close. Between windows, the walls are marked with graffiti. Not the quick words you see on the highway, but large, oversize letters, or characters drawn like cartoons. Only they’re not funny. They’re serious, telling the story of something I don’t know.

My mom disagrees. She’s an urban designer, which means she helps to decide where buildings go and how people use them. So something like graffiti drives her crazy. She’s glad we don’t have much of it in Dobbs Ferry. But I wish we did. When we come to St. Vincent Ave, I end up with so many new words in my notebook.

Today we squeezed our Subaru into the last parking space. We were lucky, because the rest of St. Vincent Ave was closed off. All along the sidewalks, there were booths lined with people selling things. I could smell the smoky scent of barbecued corn and refried beans cooking nearby.

“It’s a street fair!” Ana said, excited.

“Can we look around?” Cheetah begged. “Can-we-can-we?”

My parents agreed as long as we made our way to the furniture store. So we walked along St. Vincent Ave, Ana and me on one side, my parents and Cheetah on the other. At a table with hats and scarves, Ana took a picture of me in a tie-dyed cap with an orange flower on it, which looked ridiculous over my big, frizzy hair. I could see my shadow next to hers on the ground, hers lean and tall, mine short and round with hair sticking out from under the hat.

While Ana tried on the same cap, I drifted to the next table, where there was a man and an elderly woman selling jewelry. I wouldn’t have noticed them except they were arguing, their voices low and tight, like they were yelling with the volume turned down.

“How can you wear that?” asked the man, his face craggy like the side of a cliff. “Remember the train station. It’s not safe.”

Wear what? Then I noticed a brightly colored necklace around the woman’s neck.

“I had to wear something,” she said. “And a person selling jewelry can’t be wearing an apron. Besides, you’ve been obsessing over it like a fool for years. I have a mind to sell it away today.”

The man almost leaped out of his chair. “Don’t you dare, Ma! Put it away!”

For a moment, she didn’t say anything as they glared at each other, like two burning coals in our backyard grill. I was fascinated by their game of chicken. Who would win?

The woman finally gave in. “Fine,” she said. She undid the necklace and laid it on the table. “Now, why don’t you run along and get me some lemonade?”

He let out his breath and ruffled his hair up so that it reminded me of a bird’s nest. “I’ll do that, Ma. But put it away, okay?” Then he stood up, and he was like a tall building blocking the sun. But then, anyone next to me seemed like a tall building. He peered at me for a moment, his eyes gray against his olive-toned face, and walked away.

The woman was watching me, too, as I stood at the edge of the table, next to a tray of earrings. “All completely handmade,” she said, trying to sound friendly, and not like she’d been fighting with her son a few seconds ago. “They’re made from healing crystals, great for health.”

I nodded. While she spoke, I stared at the necklace on the table. I knew I shouldn’t ask. She probably didn’t mean what she said to her son. “Is that for sale?” I said.

She saw what I was looking at and glanced down the street. I guessed what she was doing. She was checking to see if her son was coming back. After a moment, she picked up the necklace, the one she had been wearing a minute ago, and held it out to me.

I took it from her. I wanted to know what the big story was, why the craggy-faced man was so angry in the first place. It was a pendant the size of a checker piece, on a leather string. At first, I thought it was just a flower, but then I saw something in the middle, a symbol bordered by purple-and-pink petals.

“I’ve seen this before,” I said suddenly. “I know someone with the same necklace.”

“Is that so?” asked the woman mildly. “It was popular for some time.”

I remembered Margaret wearing hers when she and Allie lived next door. But what was so special about this necklace? I turned it over. In tiny letters, a single word was etched: keeper.

“Handmade enamel, silver plated on the back. It’s an Indian peace sign. Indian like you. You’re from India, aren’t you?”

I nodded, though I hated being asked that. Like, Ana never gets asked if she’s from Norway. So I added, “My parents were born there, but I’ve lived in Dobbs Ferry my whole life.”

The woman brightened. “Oh, I used to live near Dobbs.”

We talked about the construction going on with the Aqueduct Trail and the waterfront. I let her do most of the talking while I looked at the pendant. I was never good at figuring out what to wear. I wasn’t pretty like Ana or stylish like my mom. But I could picture myself with this necklace. And maybe some of the girls stopping me in the hall at school to say they liked it. Even if that kind of thing never happened to me.

“How much?” I asked. I could still see the storm in her eyes left by her son. But would she do it? Would she sell me the necklace in spite of him?

Her face puckered. Then she said, “Seeing you’re from Dobbs, I’ll let you have it for five.”

Five! Didn’t she say handmade? It was a good price. “I only have four,” I said.

“Huh. A girl with a budget,” she said gravely. “You know what it is, right?”

What it is? Wasn’t it just a necklace? “It says ‘keeper’ on it. Is that the name of the person who made it?” Maybe it was the name of her son. Though he didn’t look like a Keeper to me.

She shook her head. “It’s a finders necklace. You know, finders keepers? Every necklace has one of those two words on the back. It tells you what sort of person you are. This one says you’re somebody who keeps things.”

“Oh.” That didn’t seem like much to me.

By now, Ana had joined me, and she was wearing the tie-dyed cap. Behind her, I saw something else. The craggy-faced man was coming back.

The woman must have seen him, too, because she said, “You have a deal. Four it is.”

“Wait up, Myla,” Ana called as I hurried across the street, just as the man reached the table. I could feel his eyes on me, but what was he going to do? I’d bought the necklace, and now it was mine.

At the furniture store, Mom saw the necklace I was wearing. “Where did you get that?”

“A woman sold it to me for four dollars. Margaret has the same one. Do you remember?”

My parents did not.

“She said it’s an Indian peace sign,” I said. “Indian like us.”

Dad looked more carefully. “I see,” he said, pushing up his glasses. “It’s an Om.”

“What’s an Om?” Ana asked.

“A two-letter word,” Cheetah said.

Dad pointed to the pendant. “It’s this symbol. I suppose you could call it a peace sign. But it’s more than that.” He explained how in yoga, the sound our mouth makes when we say Om is very important. I guess he knew because he’d been doing yoga for as long as I could remember.

“But it’s not the only two-letter word,” Cheetah went on. “There’s ‘ai,’ which is a kind of sloth. And ‘xu,’ which was a coin used in Vietnam. And in Scrabble, you can—”

“Stop,” I said. Cheetah was a spelling whiz, which meant we had to quit family game night because he always beat everyone at Scrabble. But that didn’t stop him from talking about it.

“What about ‘at’?” Ana asked. “And ‘it’? There are lots of two-letter words.”

“Yeah, but those are common,” Cheetah said.

Ana laughed. “You’re hilarious.”

She was always saying that to my brother, even though I didn’t think he was particularly funny. It was weird how they got along so easily, when I hardly spoke to Ana’s little sister.

I fingered the cool back of my necklace. “Om,” I said to myself, testing out the sound i

n my mouth. It felt rich. Like a piece of chocolate.

Inside the store, the salesman showed us a platform bed eighteen inches above the floor, six inches taller than my cinder blocks. Mom said that was “nothing,” even though you’d think for an urban designer six inches was everything. Like falling into the space between the train and the platform. Six inches could mean the difference between life and death.

“Myla, you brought a ruler?” Ana asked, watching as I measured.

“She’s scared of sleeping on a bed,” Cheetah explained to the salesman.

I gave him a shove when my parents weren’t watching. By now, I was tired of looking like a freak, so I said yes to the eighteen-inch-high bed. Then I went to the bathroom.

As I washed my hands, I studied my reflection with the necklace on. Would people finally notice me because of it? I’ve thought about it before, about being noticed, because I’m short and I have thin eyebrows and a thin nose, and I’m not the most smiley person. My hair is frizzy and isn’t a true Indian black like my parents’, more a dark brown with highlights you only see in the sun. That sounds interesting, but most people don’t notice the highlights—or me.

Just then, the door to the bathroom opened. I thought it was Ana, but it wasn’t her. Or even a girl. It was the craggy-faced man from the jewelry table.

“That necklace,” he said, his voice like gravel. “I want it back.”

At the beginning of summer, Ma bought Randall and me each a pair of Air Jordans. She got them off the street near St. Vincent Ave, and probably they were fakes, but when you put them on, you hoped they weren’t. Like, maybe the dude was selling them cheap because he needed the cash. There was something sweet about the sound of the new rubber on the sidewalk, the way it squeaked when I stopped in my tracks. I wore my Jordans all summer, even when my feet got sweaty and the shadows of Michael Jordan on the sides cracked. I wore them because Randall did, and it was one way of telling the world we were brothers—though Randall probably didn’t see it that way.

The Unexplainable Disappearance of Mars Patel

The Unexplainable Disappearance of Mars Patel Vanished

Vanished Finding Mighty

Finding Mighty